Articles: The Island of the Lotus Eaters

Charting the Future Landscape of Djerba and pondering the future landscape of Jerba, the Island of the Lotus Eaters.

Charting the Future Landscape of Djerba

by Khadija Ghezaeil

Come back to the shore of the odyssey, to the isle of lotus-eaters, Djerba, greatest island of Tunisia and North Africa captivating Ulysses and his ship comrades 3000 years ago.

In the legend, the Lotus-eaters were convivial to Ulysses’ comrades, feeding them on the lotus. “Whosoever of them ate of the honey-sweet fruit of the lotus, lost any wish to bring back word or to return, but there they were fain to abide among the Lotus-eaters, and forgetful of their homeward way”, related Ulysses (1).

Through history, the mystical charm of the island did not fade away. Having faith that if there is magic on the planet, it is most contained in water, the lotus-eaters have fought tooth and nail to preserve their Eden. Considering the unfortunate results of modern socio-economic development and increasing urban pressures deeply affecting the island and slowly but surely menacing its natural topography, it is curious how, intuitively, these locals succeeded in their battle against time, let alone nature itself.

Ever since the mid-nineteenth century, islands provided the ideal setting for investigational missions conducting fieldwork experiment in biological evolution and natural history. The study of island biogeography and natural science demonstrate how, exposed to different kinds of marine and climatic turbulences, Island ecosystems are fragile and vulnerable; compared with most continental landmasses, their ecological units namely their fauna and flora, evolutes in physical isolation.

Starting off with Charles Darwin’s (1809 –1882) orthodox and essential view of islands as insular and isolated ecospheres, the theory of island biogeography expanded all the way through the late nineteenth century (2).

Darwin’s theory of island isolation minimizes the selection of island species inspecting a regular “stasis” in their faunal and floral development, a stasis broadened in the twentieth century by Island biogeography researchers and social anthropologists such as H. Kucklick (3) , W. H. R. Rivers, C. G. Seligman, who, approximating W. C. Haddon, examine the evolution of island natives as “conservative and traditional” on one hand, identifying them as “backward and savage”, on the other (4).

But we can ask the question whether this orthodox image is applicable to the Mediterranean, and how relevant it is to the present and past Mediterranean island societies.

The question of appropriateness is raised by John Cherry (5) in his review of Mediterranean archaeology. He not only comments on the many models and analogies borrowed from Oceania, but to make the principles of island biogeography worthy of application, he also assesses its relevance to the Mediterranean islands “given that only in the Pacific Ocean do islands have the distance from continental mainland” (6) .

Comparing Djerba to other Mediterranean islands at the level of human density, Giorgio Marcuzzi finds out that it is as dense as some populated Italian provinces like Friuli-Venezia, Giulia, Toscana, Marche… inhabited since many centuries, sometimes two millennia (Etruria, now Toscana) (7).

As regards the preservation of the island of Djerba, the only reference Marcuzzi finds in bibliography is that of Di Castri, Baker & Hadley in a UNESCO/MAB publication, Ecology in practice, where Gonzales Bernaldez, El Cadi and Perelman write “Isle of Djerba case study”.

A detailed list of the threats to the island environment, according to Marcuzzi, includes: mounting anthropization, human density, agriculture, grazing and Tourism. The relentless pumping of water from pits, with a probable salinization of the water table, is harmful to both invertebrates and plants. The excavation of clay for handicraft is another threat to landscape. Grazing is bringing about devastating coastal erosion, a reduction and sometimes disappearance of coastal dunes because of the destruction of local vegetation, notably the gramineae plants. (8)

Revisiting history thirty ancient centuries, not two or three, Djerba has positively stood for a distinctive peopled Mediterranean atoll on account of its unremitting serene and friendly disposition bewitching an entire Mediterranean and global community, boarding its shores.

Little did I know about the prehistoric interest of citizens of Djerba in ecological and biogeographical issues. Environmentally friendly, ecologically aware, the antediluvian residents called upon the implementation of early measures defensive of their landscape characteristics.

Working against the clock, the Association for the Preservation of the island of Djerba (Assidj), established in 1976, is dedicated to developing the highest standards of awareness and proficiency for the sake of the preservation of the Island. Its members are public and private sector professionals as well as environment researchers and amateurs who promote ecological activism and alternative ways of savoir-faire and decision-making in light of the eminent environmental issues menacing the island of Djerba.

Bridging the gaps between the decision-makers at the top and the laymen at the bottom, the organization seeks beyond all to arouse mass consciousness as to valorize the fringe benefits of the island historical commitment to urban renewal, land redevelopment, landscape urbanism and horizontal architecture.

In his article ‘Storey Building, but then what?’, Mohamed Gouja, a musicologist, and anthropology researcher digging in the archeology of Djerba, denounces storey and vertical structural building.

Interesting to know that, unacquainted with the theory of landscape urbanism established only in the late twentieth century decades, the islanders have long before fathomed the necessity to advocate architectural designs that go in tune with the island ecosystem.

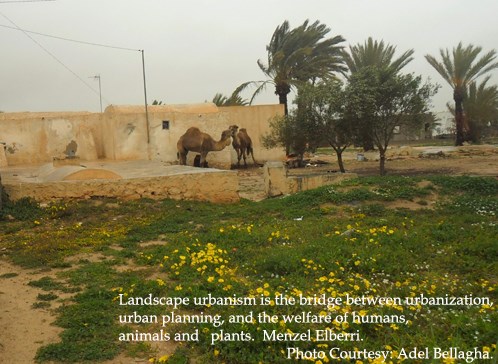

Michael Cote (9) identifies Landscape Urbanism as an emerging field that recombines the art of landscape architecture, urban planning, human wellbeing and ecosystems, along with community involvement in the built environment process.

Likewise, Charles Waldheim argues that landscape Urbanism is the foremost contestant in the struggle for intellectual prevalence in the shaping of 21st century metropolis. The theory contends alternative practices and takes on more organic guidelines running on behalf of environmental defense and ecological resurgence.

Calling upon the ongoing global environmental calamity, N. Chomsky builds a fire under contemporary population:

The most critical immediate problem civilization faces is environmental catastrophe … The countries with large and influential indigenous populations are well in the lead in seeking to preserve the planet. The countries that have driven indigenous populations to extinction or extreme marginalization are racing toward destruction (10) .

Resolving the kind of ecological life they sought for the upcoming generations, Djerbians, (residents of Djerba) instinctively adopted the building blocks of Landscape Urbanism principally through the endorsement of landscape architectural models and the adherence to horizontal construction, a cultural and urban dividend coming out of the cluster of historical, climatic and natural attributes of the island.

In this regard, Waldheim makes claim (11):

The efficiency- the ability to produce urban effects traditionally achieved through the construction of buildings simply through the organization of horizontal surfaces- recommends the landscape medium for use in contemporary urban conditions increasingly characterized by horizontal sprawl and rapid change.

As a model for urbanism, Landscape urbanism pays attention to the surface conditions- not only configuration, but also materiality and performance allowing designers to activate space and produce urban effects without the weighty apparatus of traditional space making (12).

As capitalism is changing the world, requests calling for the need to adapt the island overall urban policies to the new socio-economic present-day obligations are getting bigger. Because of the constant land trade inflation, and the contemporary prominent local and global economic crashes, many would vote against the perpetuation of landscape urbanism and the abandon of horizontal architecture, a land-consuming traditional model, they contend, in favor of vertical or also storey structural design. As a less costly model of urban planning and development, vertical building is revealed to be able to accommodate and encompass contemporary building needs.

With its highest quality manufacturers and experienced professional installers, vertical buildings offer different styles of structure not only for common indoor habitats but for most industry application, as well.

Quite the opposite, disproving the inappropriateness of landscape urbanism in the present day, the activist attests that notwithstanding the emergence of New urbanism with its selection of storey built form, landscape urbanism remains a more ecologically-based approach ranking at the forefront of sustainable urbanization and endurable development of the island.

The image of Djerba as a likely skyscraper city in the future possibly sounds stunning to those proponents of vertical urbanism and storey building. If a necessary evil however, I just can’t help but recall Stephen Spender’s poem ‘The Landscape near an Aerodrome’ (1933):

Then, as they land, they hear the tolling bell Reaching

across the landscape of hysteria, To where larger than all

the charcoaled batteries And imaged towers against that

dying sky, Religion stands, the church blocking the sun.

Notes:

1 Homer. The Odyssey, Book 9.

2 Galapagos Islands were Darwin’s first fieldwork expedition.

3 Kuklick, H. 1996 Islands in the Pacific: Darwinian biogeography and British anthropology. American Ethnologist 23: 611–638.

4 Rainbird, Paul. The Archaeology of Islands. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, New York, 2007.

5 Cherry, J. F. Mediterranean island prehistory: what’s different and what’s new? Ed. S. Fitzpatrick (.) Voyages of Discovery: The archaeology of islands. Praeger: Westport, Conn, 2004.

6 Rainbird, Paul. The Archaeology of Islands. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, New York, 2007.

7 Giorgio Marcuzzi. MEDITERRANEA SERIE DE ESTUDIOS BIOLÓGICOS 2005 Época II Nº18.

8 Ibid.

9 Cote, Michael, Landscape Urbanism, Fetish? (Spring 2008), UMass – Amherst.

10 Can Civilization Survive Capitalism?

1 Waldheim, Charles. The Landscape Urbanism Reader. Princeton Architectural Press: New York, 2006.

13 Stan Allen cited in Waldheim, Charles. The Landscape Urbanism Reader. Princeton Architectural Press: New York, 2006.

Comments: 0

There are no comments yet, be the first to write a comment!

Available for freelance